The Practice Success Prescription: Team-Based Veterinary Healthcare Delivery by Drs. Leak. Morris Humphries

Thomas E. Catanzaro, DVM, MHA, FACHE, DACHE

1970s: Job Descriptions, Standard Operating Procedures, and Management

This began the era when everything about veterinary practices started to become "standardized" for better effectiveness. Dr. Ross Clark started to read literature outside the profession and brought that information to meetings, tailored to veterinary practices, and he always gave credit to his sources. In this era, the production-animal doctor/manager did not have to think or create a new environment for "small animals". They just funneled the management documents and forms, so the small animal practice would be okay.

1980s: Mission Statements and Staff Policy Manuals

This was the first move towards discovering we were actually in a business, requiring that we defined our business direction, and subsequently providing the staff the long-deserved knowledge and expectations of the practice owners. Many trees were killed to build very thick staff policy manuals that were too detailed to read, much less remember or follow. Yet, some enterprising consultants promoted their version of a staff manual as the end item to end all practice strife, comprising pirated forms, procedures, and concepts proliferated from self-defined management "experts". Further, they seldom gave credit to their sources. Some mission statements were so long, they needed a legal sheet of paper, small type, and narrow margins just to fit it in the frame on the wall. That was the practice's real goal, since those type mission statements were too long to remember anyway.

Early 1990s: Practice Philosophy and Leadership

The revolutionary discovery, during this period, was that we could not manage a horse to water and make it drink. We either could lead it to water to drink on its own, or we could stomach tube it for its own good. World War II-style leadership was shared by many consultants, and it was only fifty years out of date for the current generation. Then Covey, Hershey, Blanchard, Catanzaro, Bennis, Peters, Juran, Deming, and others started to publish the modern thesis for the professional leadership environments. They used terminology that could be understood by most of the small business masses, often composed of people without advanced management degrees.

Late 1990s: Vision and Client-Centered

The great management speakers finally started to share the fundamental fact that if the front door does not swing, there is very little value of being a self-proclaimed expert inside your own walls. If you did not know where you were going, or your staff did not know where the practice was going, how would anyone know when you got there?

New Millennium: Core Values and Patient Advocacy

The Boy Scouts have twelve points to the Scout Law, three "duties" in the Scout Oath, and three Aims of Scouting. If a Scout leader develops a program for the Scouts that does not embrace these core values, the program does not survive, nor does that "leader".

In the new millennium, the concept of "core values" flowed into veterinary practices. The smart practitioners started to speak for the patient in terms of "needs" rather than "recommendations. Clients are not trained to make the choice from options, or understand what is needed, from a list of "recommendations" and other "waffling" terms. Ensuring the client's peace of mind became a mantra for many companion animal practitioners. Some did it with sincere and meaningful communications about the pet's "needs", while a few others tried to do it with discounts. Incidentally, discounts have never attracted the better clients, and discounts never proved a profitable business decision. They are pure net being given away.

Today: Standards of Care => Continuity of Care

Inviolate core values gave rise to establishing expectations for quality veterinary healthcare delivery. An AAHA survey of client compliance revealed that the lack of core values and/or consistent standards of care between practitioners in a practice were the key problem in client compliance. The days of the solo practitioner in a pick-up truck ,driving alone from farm to farm, were gone, and so must go the habits of the solo doctor. Consistent standards of care between providers in the practice allow a continuity of care by staff and other providers, as well as enhanced wellness of the patients, and better satisfaction within the clients.

Tomorrow: Team-Based Healthcare Delivery

The days of underpaying doctors and staff will be coming to the end of a long road of pennies-per-hundred-weight (cwt) of the ambulatory production veterinarian. School debt does not allow poverty wages, and career-minded staff deserves to have their own quality of living from a single job. Production pay, profit sharing, and fiscal recognition for excess earnings and excess savings by staff teams managing programs will replace tenure-based raises.

Within Ten Years: Virtual Veterinary Practices

We cannot hide from the electronic media and Internet community. Remote telemetry has entered human healthcare in remote areas, and it will enter the senior citizen's household. Just hook White Fang to the computer, and some virtual "talking head" will diagnose and prescribe for the most common syndromes, and bring only a few animals into the practice for diagnostic work-ups.

Within Twenty Years: Affiliated and Merged Veterinary Practices

The economies of scale and cost of diagnostic tools will cause veterinarians to start cooperating as they did in the 1970s, when we were all colleagues. There will be pockets of independent practices, mostly in rural America, but the desire for a balanced lifestyle will cause individual hours to reduce, production to increase, due to staff leveraging, and net income to become a benchmark, rather than gross and average client transaction (ACT).

Now on with our saga of the true story.

|

A True Story: Part 3

Our single-owner doctor of the ninety-four-hundred-square-foot, six-year-old hospital knew his staff was dysfunctional, and wanted us to come in and shape them up. As you may recall, both the doctor and practice manager avoided confrontation, and loved to point fingers at others. The practice manager was moved out of the hospital management role before we left, then assigned to the boarding, grooming, and a new, 501.c.3, not-for-profit operation to fund the kitten programs. The office manager was elevated to the new practice manager.

The doctor's wife loved to shop the distributors. She left the practice in a due out status for most of the week, since getting the lowest price was more important than treating the animals with the most efficacious drug. The doctor would tell the practice manager to order the drug, but not tell his wife that they were doing it. We initiated vendor stocking before we left the on-site, as well as a VetCentric account for the special order nutritional and drug products, all through the NEW practice manager, to eliminate most of the inventory problems.

The number one associate doctor virtually never came in on time. Instead of confronting the doctor, they made excuses for him, delayed staff meetings until he came in, and never "expected him" to arrive for morning appointments. This dude set his own hours, and no one seemed to care that his discourtesy to the staff was a lifestyle of disruption to the practice planning. The other associate had no consultation room skills, so they allowed her to stay out on ambulatory and house call, which means she was subsidized by the practice to be a low producer. Both were shifted to production-compensation-only before we left the on-site.

The single-owner doctor tried to staff the front and back all morning by himself, and sucked staff behind him like a black hole in the outer reaches of the galaxy. As we left, we hired the relief doctor, a smiling and competent post-internship gal, as a full-time associate. We then moved the owner to a split-shift schedule, working only one zone, specifically outpatient or inpatient/surgery, for half the day, then changing zones mid-day. |

There is a greatest practical benefit in making first mistakes often, as well as the best failures early in life. For he who is not trying something new will never learn to fail or recover, and those who never move from where they have always been will never stumble. - Thomas Huxley, as amended by Tom Cat

The Feeble Evolutionary Efforts

In the early 1990s veterinary medicine discovered the strategic planning process, and started to use it at the association level. They usually hired expensive facilitators, who did not really know this profession, and they worked with the boards, who were only experienced in the past and were secure with what "has always been". In the grand scheme of things, most of the early strategic planning efforts were built on assigning blame. And the more recent "expert" studies spent great money and effort to do the same thing. This is common, since most veterinarians have been restricted to a closed practice environment, and "future-think" was not a common pastime. When they got out of the practice, they associated with peers from the same era and with similar habits, causing the past to become a cornerstone of the planning process. Most strategic plans were made for five years, but after the first year, and elected officer rotation, it stayed on the shelf and collected dust.

Figure 5: Strategic Planning SWOT Matrix

|

Strengths

Positive attributes concerning the facility, staff, or services of the practice. |

Weaknesses

Shortfalls in skills, equipment, or people within the practice setting. |

|

Opportunities

Community changes that provide a market potential for the practice. |

Threats

Community players or government regulations that hinder the practice. |

The above standard, four-quadrant matrix reflects the thought process required to make a successful plan. The logic for the assessment process was solid: look inside and outside the organization, from the positive and negative perspectives. It causes an assessment of the resources available inside the practice, as well as within the surrounding environment. It balances good news with bad news. By the late 1990s, the strategic planning process started to fall from grace in veterinary medicine, so the "powers" started to hire large consulting firms to conduct surveys about the profession. Again, without the insight about healthcare delivery dynamics, and without sensitivity to the human-animal bond, most all reports were supply-and-demand based. The new millennium saw the profession assign blame again, with the KPMG Mega Study, which was talked to death for more than two years, while the people trying to make a living inside the profession wanted alternatives and actions, rather than just assigned blame.

Let's return to our true story for a moment.

|

A True Story: Part 4

The practice was markedly better than the practices on either side on the same road, as, yes, quality is relative. Our veterinarian-owner even did a residency on the West Coast with a renowned internal medicine specialist. The practice to the east if his was a "low cost" clinic, offering deeply discounted spays and neuters, advertised on their sign in bold letters. Their parking lot was usually empty. The practice to his west was a mixed animal practice, injectable anesthesia only, with minimal services, with dentistries "unneeded" for farm dogs or barn cats. Their parking lot was usually empty also.

When asked, "Which animal, what species, what age, what sex, what breed, is it always safe to do general anesthesia without any form of blood work?", the doctor's answer was "none." Yet many surgeries had no lab work, and the ones that had blood results, the atypical lab findings were not followed until resolved.

When asked, "When is it humane to leave an animal in pain?", the doctor's answer was "never." Yet many surgeries had no preemptive pain assessment, now required by the 2003 AAHA Standards, and no post-surgical pain management plan.

Animals were placed into boarding, or into the surgery ward for P.A., with no vaccination history, no wellness screen, and/or no physical examination. Yes, the doctor knew it was a liability, but he made excuses for a variable standard of care and the short cuts being taken. They have always done it that way! |

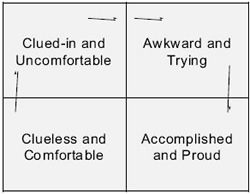

We have used the four quadrant-system, when explaining change (see Figure 6), and as part of the assessment phase (see the VCI® Signature Series Monograph Strategic Assessment & Strategic Response).

| Figure 6: Change Process |

|

|

| |

In the early 1990s many "accountant-minded" consultants and articles went into detailed cost control measures. Some of these "purchase order-based" cost control systems cost so many staff duty hours that the savings in product control was offset two-fold by manpower obligations and resupply slowdown. The need to control expenses is a mandate. However, for veterinarians in a mature practice, a one percent savings effort takes about as much energy and dedication as learning a new income center that earns another ten percent income. We can usually cause a greater than three percent "pure expense savings" in inventory management if we just convert a practice to vendor stocking, and concurrently negotiate a "best price" based on the historical annual use, billed on an "as-delivered" basis. Concurrently, vendor stocking allows staff to return to their primary duties of animal healthcare delivery.

The "one answer" management cure is like the "one medicine" cure. It only exists in the minds of the naive or uninformed.

The veterinary management emphasis of recent years has been to increase fees. And if that did not work, increase fees some more. Fee increases have their place in any business, but addressing the problem with a single solution of "fee increase" ignores the recessionary economy group-think of clients, and is self-limiting. We find practices even now, who know they have raised their fees too high too fast and have moved into a perpetual discount mode to balance their practice. This has been manifested in the quest for the highest average client transaction (ACT), the holy grail of veterinary economics advocates.

The NCVEI continues to stress fees in most every survey they do. This is the special task force group that was formed to address the shortfalls and challenges offered by the 1999 KPMG Mega Study. To illustrate the "past-tense thinking" of the NCVEI, surgery was defined by this task force as "fee for hospitalization, anesthesia, and surgery, as quoted to telephone enquirers. The fees for routine surgery do not include preoperative blood work, intra-operatory fluids, or other contiguous services that are not common to all patients and practices", such as pain management? This is antiquated thinking and reflects substandard practices, but it appears that it is being institutionalized by NCVEI in their survey efforts!

Ask yourself this. If your favorite restaurant started to increase its menu prices every quarter, how many fee increases would it take before you started to look for different restaurants? A more accurate analogy would be the dry cleaners, since you do not have any way of measuring the long-term quality effect on your clothes of their work. What if your favorite dry cleaner started to increase per piece prices every quarter? How many fee increases would it take before you started to look for a different dry cleaner?

Price is not the only issue for breaking client bonds. Poor service, such as not being seen on time, poor explanations, as not communicating at the client's level of understanding, or poor handling of the animals, as in roughness or causing fear, will break the client bond faster than price changes.

People forget how fast you did a job, but they remember how well you did it.

During this same time period of the 1990s, we have taught our consulting partners to look into their own programs and increase client return rates, then to assess new programs and increase patient return rates. Here are some generic examples of what we tailor to practice catchment areas and practice paradigms:

Pre-emptive pain scoring (Reference: required by new 2003 AAHA Standards for Hospitals):

0. No pain.

1. Maybe there was pain.

2. There should be pain (abrasions).

3. Post-op soft tissue/large wounds.

4. Dental extractions.

5. Multiple extractions.

6. Declaw, fractures, blunt trauma.

7. Head pressing attitude.

8. Pancreatitis, severe fractures.

9. Extensive burns, septic gut.

10. Patient screaming!

Human-animal bond wellness programs (Reference: Promoting The Human-Animal Bond in Veterinary Practices, Iowa State University Press Text):

Life cycle consultation (go to www.npwm.com).

Life cycle consultation (go to www.npwm.com).

Patient ID kit.

Patient ID kit.

Day care services.

Day care services.

Behavior management:

Behavior management:

House training.

House training.

Socialization.

Socialization.

Family fit.

Family fit.

New owner orientation.

New owner orientation.

"Puppy Clubs".

"Puppy Clubs".

"Kitten Carrier Class".

"Kitten Carrier Class".

Nutritional advisor.

Nutritional advisor.

Parasite prevention.

Parasite prevention.

Dental hygienist.

Dental hygienist.

Whelping services.

Whelping services.

Genetic predispositions:

Genetic predispositions:

www.upei.ca/cidd/intro.htm (North America).

www.upei.ca/cidd/intro.htm (North America).

www.vetsci.usyd.edu.au/lida (Australia).

www.vetsci.usyd.edu.au/lida (Australia).

"Golden Years" program.

"Golden Years" program.

Hospice services.

Hospice services.

VIP boarding.

VIP boarding.

Pet placement (AVMA).

Pet placement (AVMA).

Dental scoring: Door to door total fee pricing suggestions (Adapted from:Medical Records for Continuity of Care & Profit, VCI® Signature Series Monograph):

Grade 1+: Prophy," early dental cleaning", colored plaque on molars (bacteria), gingiva fully attached, priced at thirty-three to forty percent of the Grade 3+, due to shortness of procedure and the almost total staff-based procedure. This actually needs to be priced at or about the fees being paid for client dental cleaning procedures in the community for best acceptance, which is approximately $134.

Grade 1+: Prophy," early dental cleaning", colored plaque on molars (bacteria), gingiva fully attached, priced at thirty-three to forty percent of the Grade 3+, due to shortness of procedure and the almost total staff-based procedure. This actually needs to be priced at or about the fees being paid for client dental cleaning procedures in the community for best acceptance, which is approximately $134.

Grade 2+: Prophy, "late dental cleaning", colored plaque on incisors and molars (bacteria), red (pain) gums, gingiva less than twenty-five percent detached pockets, for three per inpatient two hours, approximately $254. X-rays in late Grade 2+ are essential for an accurate healthcare delivery plan (old term: estimate), but imaging fees are not included in this price.

Grade 2+: Prophy, "late dental cleaning", colored plaque on incisors and molars (bacteria), red (pain) gums, gingiva less than twenty-five percent detached pockets, for three per inpatient two hours, approximately $254. X-rays in late Grade 2+ are essential for an accurate healthcare delivery plan (old term: estimate), but imaging fees are not included in this price.

Grade 3+: Oral Surgery, tartar, disease with twenty-five to fifty percent gingiva pockets, imaging required before healthcare plan can be rendered, priced at traditional single price for one hour of doctor-involved inpatient care, approximately $400+.

Grade 3+: Oral Surgery, tartar, disease with twenty-five to fifty percent gingiva pockets, imaging required before healthcare plan can be rendered, priced at traditional single price for one hour of doctor-involved inpatient care, approximately $400+.

Grade 4+: Oral Surgery, severe tartar, disease to the bone, with greater than fifty percent gingiva pockets priced at thirty-three to forty percent above traditional one-hour of inpatient care.

Grade 4+: Oral Surgery, severe tartar, disease to the bone, with greater than fifty percent gingiva pockets priced at thirty-three to forty percent above traditional one-hour of inpatient care.

Pre-anesthetic risk levels (Adapted from: Medical Records for Continuity of Care & Profit, VCI® Signature Series Monograph, and the Controlled Substance, VCI® Signature Series Monograph):

Minimal: All A-OK.

Minimal: All A-OK.

Slight: Blip on PE/Lab and/or client deferred needed care item.

Slight: Blip on PE/Lab and/or client deferred needed care item.

Moderate: Limiting condition.

Moderate: Limiting condition.

High: Incapacitating condition, shock, etc.

High: Incapacitating condition, shock, etc.

Grave: Death is imminent.

Grave: Death is imminent.

Body condition scores (Reference: The traditional five-point system causes many doctors to use decimal point numbers, making computer entry much more difficult, so we prefer the nine-point system from Purina Pet Care Center, and expand on it in, Promoting The Human-Animal Bond in Veterinary Practices, 2001 Iowa Stae University Press text.):

1. Emaciated, lumbar vertebrae.

2. Very thin, ribs very visible.

3. Thin, waist tuck.

4. Underweight, ribs palpable.

5. Ideal Weight.

6. Overweight, fleshy ribs.

7. Heavy, waist absent.

8. Obese, rounded overweight.

9. Grossly obese, fat over spine.

Hospitalization levels (Adapted from: Medical Records for Continuity of Care & Profit, VCI® Signature Series Monograph):

Level I -- day care: Is sixty to sixty-five percent of the price of single night in "one fee" hospital.

Level I -- day care: Is sixty to sixty-five percent of the price of single night in "one fee" hospital.

Level II -- o.d./b.i.d. txs: The usual price of single night in "one fee" hospital.

Level II -- o.d./b.i.d. txs: The usual price of single night in "one fee" hospital.

Level III -- t.i.d./q.i.d. txs: Is fifty percent above price of single night in "one fee" hospital.

Level III -- t.i.d./q.i.d. txs: Is fifty percent above price of single night in "one fee" hospital.

Level IV -- IV cases: Is double the price of single night in "one fee" hospital.

Level IV -- IV cases: Is double the price of single night in "one fee" hospital.

Level V -- ICU/CCU cases: Is double-plus the price of single night.

Level V -- ICU/CCU cases: Is double-plus the price of single night.

Inpatient nutritional scoring:

0 = Eating well.

1 = Off feed, slow eating.

2 = Purposeful NPO patient.

3 = Anorexia for one day.

4 = Anorexia for two days.

5 = Anorexia for three days.

6 = Anorexia for four days.

7 = Anorexia for five days.

Modify the above:

Modify the above:

Add 1 for mild disease/surgery.

Add 1 for mild disease/surgery.

Add 2 for febrile disease/injury.

Add 2 for febrile disease/injury.

Add 3 for severe disease/injury.

Add 3 for severe disease/injury.

The above tables and scoring systems were published in one pocket card, The VCI® Veterinary Human Animal Bond Patient Scoring Pocket Guide, illustrated at the right. It was a third in our series of pocket cards. The first was VCI® Leadership Skills, and the second was a VCI® Human Resource pocket card. The fourth in the series of pocket cards is the VCI® Winning Way. Each pocket card has been distributed at our twice-a-year VCI Shirt Sleeve Seminars ®, the oldest and most integrated three-day healthcare team training seminar in America, and our annual VCI Seminars @ Sea ®, the oldest and most consultant-diverse leadership course in veterinary medicine. There are seven consultants from four different veterinary-specific firms, who are made available to participants for the entire luxury cruise, which is a one-to-two-week training adventure for leaders in the veterinary profession.

Pocket cards are also made available to seminar participants when Dr. Catanzaro does seminars for any VMA, student chapter, regional, or national meeting. All four pocket cards, as well as applicable VCI® Signature Series Monographs, are all part of the on-site consultations we do for our consulting partners/clients (go to www.drtomcat.com).

Money is not required to buy one necessity of the soul. - Thoreau

As consultants, we prefer a lower ACT per visit, and more visits per year per pet, especially during this recessionary mind-set period of America. Which would you prefer to experience? Two visits a year at $137 each, or four visits per year, plus another one being a courtesy recheck by a nurse, maybe with a very small product sale? If there were four visits at $93 per pet, that is only $142 extra per year per pet, but it is a quarterly opportunity to assess the animal. If one dog year equals seven people years, as our clients believe, this is about equivalent to the animal stewards seeing their own physician once every two years. And the key question, when developing a healthcare delivery team, which of the following lights the fire in the belly: better healthcare surveillance for the animal, or a higher act? Well, DUUHH!

Only Congress believes we can be taxed into prosperity.

At the beginning of this millennium, in both human healthcare and veterinary medicine, there was one common factor present, whenever the strategic plan provided enhanced positioning within the healthcare community. The organization with the best gain had put "people concerns" into their strategic plan. When the focus was on profit rather than people, failure occurred. In retrospect, the detailing of the profit motive was counterproductive to motivating the people in the "caring professions" of healthcare delivery. When will veterinary medicine ever learn?

In discussing the VCI® Pocket Cards above, I mentioned our twice-a-year VCI Shirt Sleeve Seminars ® and our annual VCI Seminars @ Sea ®. We started these seminars because no one in veterinary medicine was committed to training teams. In some state VMAs, the management speakers were not even allowed to provide the same topic to technicians as to the doctors, and we could not get them to schedule seminars for client relations specialists, bookkeepers, or animal caretakers.

In the early 1990s, Owen McCafferty, CPA, and I organized, planned, and self-funded a multi-city speaking tour to introduce "Program-based Budgeting and Income Center Management", in hopes of changing the professions love affair with the gross income and ACT. We called it Catch The Wave, and, in fact, it hit many as a tsunami, overloading their paradigms and bias' so heavily, that attendees walked out numb. As we entered the new millennium, "Program-based Budgeting" started to appear in other consultants' speaking list. It was becoming a hot topic on the meeting circuit.

In 1995, VCI ® and Catanzaro & Associates, Inc., assisted by architect Larry Gates, from Gates Hafen Cochrane Architects, attorney Ed Guiducci, of Guiducci & Guiducci Attorneys, and Roger Cummings, CVPM, currently of the Brakke Group, plus four other consultants from Catanzaro & Associates, Inc., held the first seven-day leadership skills course. It was the maiden voyage of VCI Seminars @ Sea®, aboard an Alaska to British Columbia luxury cruise ship. In 1996, we started the VCI Shirt Sleeve Seminars® for healthcare delivery teams. We planned our VCI® seminars as break-even events for our firm, and to keep the prices economical enough for a practice that wanted to bring the full team of managers to a veterinary team-building seminar that was program-based.

The first book I ever published was the AAHA Design Starter Kit, and few know that I had to use my own divisional funds to self-publish that pre-architect reference, as AAHA had never published a book and thought it was too much risk. It became a bestseller immediately, so AAHA took credit for the idea, and it is now in its third edition. It is not surprising that AAHA has recently asked for a fourth edition of this pre-architect reference book.

The twelfth text in our VCI® library of veterinary-specific reference publishing was Design the Dream, and it came out in May 2003 from Iowa State University Press. It is a post-architect selection primer, with eight contributing veterinary-experienced architects. The text describes how an owner, who is paying the building's costs, can better control the design and construction teams during construction. The text also includes a chapter on the grand opening and repetitive open houses for the community.