Kevin Stafford, MVB, MSc, PhD; Vicki Erceg; Monica Kyono; Janice Lloyd; Nikki Phipps

Background

The human dog dyad goes back a long way and may have begun 15 to 40,000 years ago (Savolainen et al., 2002). This interspecies relationship has varied depending on the function the dog has served. Working dogs such as sleigh dogs may have quite a defined and non-intimate relationship with their handler but when work is combined with companionship or when the animal is owned for companionship alone then the relationship may be much more intimate. In this paper the success of the match between dog and human in three different circumstances will be investigated. The matches will include the dog adopted from an animal shelter for companionship, police dogs and their handlers, and guide dogs for the blind and their handlers.

Companion Dogs

The euthanasia of healthy unwanted dogs is probably the leading cause of death for dogs in America (Olson et al., 1991; Patronek and Rowan, 1995). In New Zealand at least 4000 dogs are euthanased in Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) shelters each year (Peter Blomkamp, SPCA New Zealand). The majority of these dogs were obtained for companionship (Miller et al., 1996) but many are surrendered by people claiming that they did not want the dog in the first place (DiGiacomo et al., 1998). Many dogs are surrendered to an animal shelter because of behaviour problems, because the owners are moving home, or have not the wherewithal to care for the dog. DiGiacomo and colleagues (1998) found that many people found it difficult to surrender the dog but circumstances forced them to do so. From studies of why dogs are surrendered to animal shelters it is hard to determine whether the surrender was due to a mismatching between the dog and its owners or merely due to circumstances that made the continued ownership of the dog untenable. In New Zealand, Phipps (2003) found that of 967 dogs surrendered to a shelter 30% were strays and 26% were puppies from unwanted litters. Of the rest (n=426) 31% were 'unwanted' by their owners which suggests a mismatch, 32% of owners had problems with time/space/money, 20% were moving house and 15% believed that the dog had behaviour problems. The behaviour problems, in order of importance, were running away, hyperactivity, aggression and barking.

Studies that look at why dogs adopted from shelters are returned give a better understanding of the dynamics of surrender and whether the human and dog are mismatched or not. In one Irish study 68% of people who adopted a dog from an animal rescue shelter reported that their dog had exhibited an inappropriate behaviour within one month of acquisition (Wells and Hepper, 2000) but only a small % of these dogs were returned. Kidd et al. (1992) found that 20% of adopted pets (dogs and cats) were returned.

In New Zealand dogs were adopted from three shelters as companion animals (Phipps, 2003). The staff at each shelter worked within defined protocols to ensure success of the adoption process. Potential adopters of dogs had to be considered worthy and to have a fenced property. A total of 494 adopters who had adopted a dog from one of 3 different shelters were identified for the survey. However only 127 (25%) of the 494 adopters could be contacted with the majority either having moved home or not being contactable.

Of the 127 people contacted 106 (83%) still had the dog and in one part of the study, 28 people who had adopted a dog considered the match success to rank at 3.18 on a scale of 1-5 with one being poor and 5 being very good. Of the 127 adoptions 21 failed due to health problems (n=1) and behaviour problems (n=20). However many of the retained dogs had behaviour problems. The rejected dogs were hyperactive, roamers or aggressive whereas the retained dogs with behaviour problems were likely to steal washing, dig gardens, bark or be wary of males. The specific type of behaviour problem influences the likelihood of the adoption being a success. In one part of this study the 10 dogs that were returned to the shelter had been adopted for the children (n=4), to replace an old dog (n=3), for security (n=2) or the adopted wanted a dog (n=1).

These figures suggest that about 16% of adopted dogs are rejected and could be considered a mismatch. A mismatch is by definition a human assessment of what is acceptable and what is not. Mismatches results from human expectations not being met by the dog. Having great expectations of a dog's usefulness with children (Kidd et al., 1992; Phipps, 2003) seems to be a particular cause of mismatching. The ability of a dog to replace a previous dog may be too high for even a well-behaved dog to fulfill.

Working Dogs

Police dogs are archetypal working dogs but may have a close relationship with their handler. The latter often depends on their dog for personal safety in dangerous tracking assignments.

In a survey sent to 120 police dog handlers in New Zealand (Kyono, 2003), 74 (67%) of the handlers responded. On a scale of 1-5 (1=not at all well matched; 5=very well matched) only 1% of handlers thought that police dogs were very well matched (5) with their handlers but 34% thought that they were personally very well matched with their own dog. Almost 20% of handlers believed that dogs and handlers were not well matched up at all. This difficulty they believed was due to a scarcity of useful dogs and a lack of choice.

In addition 12 police handlers were questioned regarding the matching of 41 dogs they had used and how they rated the dogs they were handling. When the records of the 41 dogs were analysed each dog had an average of 1.5 handlers. Of the 41 dogs 24 had only one handler, 13 had 2, 3 had 3 and 1 had 4 handlers. This suggests indeed that what the respondents to the survey had stated was true in that about 40% of dogs were taken from their initial handler and given to another presumably more suitable handler. Interestingly all of the 12 handlers interviewed had had more than one dog and the average rating of their first dog was 4.3 (scale 1=poor; 5= excellent) while their second dog was rated 3.

Police dogs are expensive to produce and successful matching is important. These dogs are generally strong-willed and tenacious and need to be handled with care. It may be difficult for novice handlers to manage tough dogs effectively and hence the transfer of dogs from handler to handler.

Working and companion dogs

Dogs used as guides for visually impaired people improve mobility (Delafield, 1974) but also provide friendship, companionship and improve social interactions (Steffens and Bergler, 1998). Matching guide dogs successfully needs to combine the physical and psychological requirements of the handler and depends on the compatibility of the dyad which may be defined as the behavioural, physical and psychological fit of the human and dog (Budge et al., 1997).

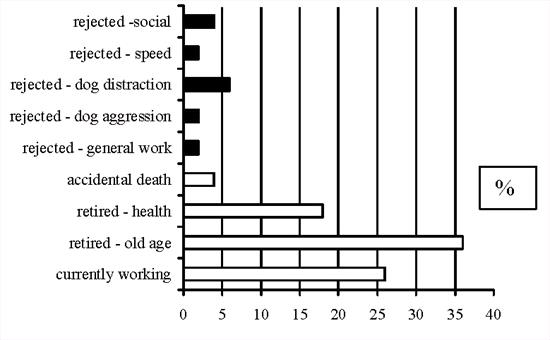

In an extensive study of guide dogs and handlers in New Zealand (Lloyd et al., 2003) about of 16% of first time dogs were rejected (Figure 1). They were rejected for behaviour (dog distraction, aggression), work including speed, and social reasons. The gender and age of handlers did not influence rejection but useful vision had an effect. Handlers with a lot of vision had a lower compatibility score than those with some vision. The dogs influence on the handler's mobility, the handler's ability to control the dog, like-mindedness of dog and handler and the dog's impact on social interactions are reliable indicators of matching success.

Discussion

Dogs are owned and used for different purposes. Companion animals taken from a shelter have a high success rate with return rates of 16% (Phipps, 2003), 12% (Alexander and Shane, 1994) and 20% (Kidd et al., 1992). A similar % (16%) of first time guide dogs were considered a mismatch by the respondents (Lloyd et al., 2003). However, a large % (40%) of police dogs were moved from their initial handler to a second handler. Police dogs and their handlers have a different relationship than that between companion dogs and their owners. The companion and social elements of the dog/human dyad may not be so important in the police dog-handler relationship and this may make the ease of transfer from one handler to another easier to come about. People reject companion dog because they have unreal expectations of what a dog can provide. It is important to assure novice dog owners or owners of a new dog that dogs may not be all that is expected and interestingly veterinary advice is closely related to success of adoption (Patronek et al., 1996).

The second dog a person owns may not meet the expectations generated by their first dog. This has been observed in police dog handlers whose second dog rated much lower than their first one and a similar trend had been noted in guide dogs.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the help from the different animal rescue shelters, Police from the Police Section of the New Zealand Police Force and guide dog users and staff of the Guide Dog Service, New Zealand

Preliminary results indicate that 16% of first guide dogs in the sample were rejected. Fig. 1 illustrates the fate of dogs in the sample, by percent outcome. Rejected dogs are shown in black bars.

Click on image to see a larger view

| Figure 1. Fate of All First Guide Dogs, By Percent Outcome |

|

|

| |

References

1. Alexander SA and Shane SM. 1994. Characteristics of animals adopted from an animal control center whose owners complied with a spay/neutering program. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 205: 472-476

2. Budge RC, Jones B and Spicer J. 1997. A procedure for assessing human-companion animal compatibility. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Veterinary Behavioural Medicine, Birmingham, UK, UFAW.

3. Delafield G. 1974. The effect of guide dog training of some aspects of adjustment in blind people. Thesis (unpublished). University of Nottingham, UK

4. DiGiacomo N, Arluke A and Patronek G. 1998. Surrendering pets to shelters: the relinquisher's perspective. Anthrozoos 11: 41-51

5. Kidd AH, Kidd RM and George CC. 1992. Successful and unsuccessful pet adoptions. Psychological Reports 70: 547-561

6. Kyono M. 2003. The New Zealand Police Dogs. Thesis (unpublished), Massey University, New Zealand

7. Lloyd JKF, LaGrow SJ, Budge RC and Stafford KJ. Matching Guide Dogs: Mobility and Compatibility Outcomes. International Mobility Conference 11; Guide Dogs of South Africa, Stellenbosch.

8. Miller DD, Staats SR, Partlo C and Rada K. 1996. Factors associated with the decision to surrender a pet to an animal shelter. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 209: 738-742

9. Olson P, Moulton C, Nett T and Salmon m. 1991. Pet overpopulation: a challenge for companion animal veterinarians in the 1990s. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 198: 1151-1152

10. Patronek GJ and Rowan AN. 1995. Determining dog and cat numbers and population dynamics. Anthrozoos 8: 199-205

11. Patronek GJ, Glickman LT, Beck AM, McCabe GP and Ecker C. 1996. Risk factors for relinquishment of dogs to an animal shelter. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 209: 572-581

12. Phipps NM. 2003. Rehoming animals from animal rescue shelters in New Zealand. Thesis (unpublished), Massey University, New Zealand

13. Savolainen P, Zhang T, Luo J, Lundeberg J and Leitner T. 2002. Genetic evidence for an East Asian Origin of domestic dogs. Science 298: 1610-1613

14. Steffans MC and Bergler R. 1998. Blind people and their dogs. IN CC Wilson and DC Turner (Eds), Companion Animals in Human Health (pp 149-157). Thousand Oaks, CA.

15. Wells DL and Hepper PG. 2000. Prevalence of behaviour problems reported by owners of dogs purchased from an animal rescue shelter. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 69: 55-65