Department of Clinical Sciences of Companion Animals, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University

The Netherlands

1. Spinal Cord Tumors

Although spinal cord tumors are uncommon causes of spinal disease in dogs and cats, they are significant once the more common problems such as disc disease and trauma have been eliminated. Older animals are usually affected although certain tumor types occur in young animals, e.g., lymphoma in cats.

Clinical signs produced by tumors of the spine are the same as those seen for any spinal disorder. Animals with spinal tumors often have initial onset of nonspecific discomfort, followed by progressive neurological deficits and evidence op spinal pain. Marked muscle atrophy is often present caudal to the lesion. Sudden deterioration in neurological status or sudden increase in spinal pain is possible, e.g., with pathological fracture of a tumorous vertebral body. In case of extradural or intradural spinal cord tumors, the tumor mass may grow slowly which gives unaffected spinal parenchyma time to compensate. Therefore clinical signs may become apparent when considerable tumor mass has already filled up the spinal canal, especially in case of cervical localization. Tumors involving the brachial plexus or lumbosacral plexus may present first as progressive unilateral lameness, and later with spinal cord dysfunction when the vertebral canal is invaded (see under nerve sheath tumors).

Diagnosis of spinal cord tumors relies on electromyography, radiography, scintigraphy, myelography, and advanced imaging techniques such as (spiral) computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Electromyography may be helpful in the confirmation of neurological disease and to determine the neurological localization for further imaging. The value of survey radiographs of the spine lies in the identification of primary tumors involving bony structures of the spine (osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma) or metastasizing tumors to vertebral bodies. Radiographs also rule out discospondylitis. In most cases of spinal neoplasia radiographs result in negative findings necessitating further imaging with myelography. Evaluation of the myelogram provides information about the location of the tumor and also its position in the vertebral canal relative to the dura mater and the spinal cord. It is important to take lateral and ventrodorsal views to allow correct evaluation of the myelogram. A cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample should be kept when a myelogram is performed; occasionally neoplastic cells may be identified in the CSF. In case the tumor is within reach, a needle aspiration biopsy may be attempted. However, in most cases of spinal neoplasia the tumor is out of range of needle aspiration because of its localization in the vertebral canal. Radiographs of the thorax are recommended in all cases with suspicion of spinal cord neoplasia. Bone scintigraphy may be helpful in the localization of vertebral bone tumors or metastasizing lesions to the spine.

CT and especially MRI, when available, are the imaging tools of choice for spinal cord neoplasia. CT and MRI allow for direct assessment of the spinal cord itself instead of indirect visualization of extradural or intradural space-occupying lesions in case of myelography. CT and MRI also allow for differentiation between normal spinal cord parenchyma and the neoplastic tissue. Based on the CT and MR images, planning of microneurosurgical procedures is possible, using the best approach with wide surgical exposure and allowing for precise dissection between unaffected spinal cord parenchyma and spinal cord neoplasia.

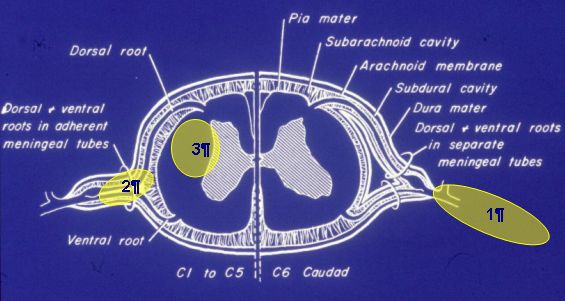

Based on the myelogram, CT, and/or MRI findings spinal cord tumors are classified in extradural tumors, intradural-extramedullary tumors and intramedullary tumors (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. |

Extradural (1), intradural-extramedullary (2), and intradural-intramedullary localization of a spinal cord neoplasia. |

|

| |

Extradural tumors

Extradural tumors are the most prevalent type in dogs, accounting for 50% of the cases. They encompass the tumors that lie outside the dura mater, i.e., vertebral body neoplasia (osteosarcomas, fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, myeloma) and metastasized extradural tumors (carcinoma, sarcoma, melanoma). In cats, the most common extradural tumor is lymphoma that may also affect the spinal cord itself (intradural localization).

Intradural-extramedullary tumors

These tumors lie within the dura mater but outside the spinal cord parenchyma. The most common are meningiomas and nerve sheath tumors (neurofibroma, neurofibrosarcoma, schwannoma; see below). Meningiomas are far less common in the spinal cord than in the brain. Nerve sheath tumors make up the majority of neoplasm in this location. When they occur in the cervical (C1-C5) and thoracolumbar spine (T3-L3) spine, signs of spinal cord compression and dysfunction are seen. Since these tumors usually lead to lower motor neuron dysfunction, electromyography is very useful to identify the nerve roots involved.

Intramedullary tumors

Intramedullary tumors (glioma, astrocytoma, ependymoma or metastasizing tumors, e.g., lymphosarcoma) occur within the spinal cord parenchyma and are the least common types.

Surgical intervention in primary spinal cord neoplasia may be considered 1) to collect tissue for histopathological diagnosis or 2) to improve spinal cord function by tumor removal and decompression. Surgical treatment is considered appropriate in extradural tumors and intradural-extramedullary tumors. In case of intramedullary tumors there is usually not a sharp border between neoplastic tissue and normal spinal cord parenchyma and surgical resection is considered palliative. Surgical approaches must be tailored to the location of the tumor and, ideally, are planned using the information available by CT and MRI. Generally, wide exposure of the tumor and spinal cord is desirable. Dorsal laminectomy is recommended in most patients with a spinal cord neoplasia in the cervical or thoracolumbar area. The 'ventral slot' approach in the cervical area is not useful since access to the spinal cord and nerve roots is limited. Also, the venous sinuses hamper an undisturbed, dry surgical field. In the thoracolumbar area dorsal laminectomy will lead to instability, therefore following tumor removal the vertebral stability must be restored using internal fixation techniques such as Lubra plates or spinal plates. The intradural localization of meningiomas necessitates a durotomy and often also a partial durectomy. The use of surgical magnification (loupes or operating microscope) makes identification of tumor margins easier. Often the neurosurgeon has to weigh the advantages of complete tumor removal including a margin against potential damage to the spinal cord leading to worsening of neurological deficits. Therefore spinal cord neoplasia removal of tumor tissue may not be complete and other therapies (chemotherapy and radiation) should be considered as follow up treatment. Methylprednisolone is administered pre-operatively (2-5 mg/kg) to minimize the effects of spinal cord manipulation.

2. Nerve Sheath Tumors (NST)

Nerve sheath tumors (NSTs) have a low incidence in dogs and most commonly involve the peripheral nerves of the brachial plexus. NSTs are benign or malignant mesenchymal tumors and they originate from periaxonal Schwann cells (schwannoma) and fibroblasts (neurofibroma/neurofibrosarcoma). Due to its mesenchymal origin the terminology for NSTs is diverse and a wide range of names has been used in the literature, e.g., neurinoma, schwannoma, neurofibroma, neuro(fibro)sarcoma, neurilemmoma, neurogenic sarcoma, and neurofibromatosis. Currently the most widely used name is nerve sheath tumor. On histological examination NSTs exhibit Antoni A or Antoni B patterns; the former (Antoni A) comprises compact spindle cells arranged in interlacing fascicles and palisades (whorls), whereas the latter (Antoni B) is less cellular, consisting of spindle cells arranged loosely and supported by edematous matrix. NSTs may occur in every large or small nerve in the body but will only receive attention from the orthopedic surgeon or the neurosurgeon when the spinal cord, cauda equina or main peripheral nerves of limbs are involved. Although most NSTs grow outside the dura mater (extradural) they may extend along the pathways of the nerve roots into the intervertebral foramen. Once inside the spinal canal they may develop an intradural-extramedullary component or even an intradural-intramedullary component (Figure 1). Clinical signs include severe, unexplained, and intractable pain, thoracic or pelvic limb lameness, monoparesis, ataxia and proprioceptive deficits. Early diagnosis and an aggressive surgical protocol maximize the possibility for complete tumor resection sparing the limb. NSTs have a high rate of recurrence, and the overall prognosis is considered poor.

At the Utrecht University eight dogs with a nerve sheath tumor were seen in which the diagnosis of NST was confirmed by imaging or histological examination of the surgical specimen. The dogs (German Shepherd, English Cocker Spaniel, Bouvier, Irish Terrier, Labrador Retriever and 3 Golden Retrievers) ranged in age from 14 months to 10 years and were referred for limb lameness, monoparesis, severe muscle atrophy, and (periodic) severe limb or axillary pain unresponsive to medical treatment. Pain was eventually localized in the upper cervical area (1 dog), in the lower cervical area and axillary region (4 dogs), in the lower back region (1 dog), and in the distal limb (2 dogs). Electromyography was performed in 4 dogs and showed denervation potentials of the muscles of the affected limb. In all dogs radiography was not diagnostic or inconclusive.

Computed tomography was performed in 5 dogs, magnetic resonance imaging in 2 dogs, and ultrasonography in 2 dogs. CT revealed a brachial plexus tumor at C6-C7-T1 in 3 dogs, an intradural-extramedullary tumor component of a NST at C6 in 1 dog, and lumbosacral disc disease together with a right spinal nerve root S1 tumor in 1 dog. MRI revealed an intradural-extramedullary tumor component of a left paravertebral NST at C1-C2 in an Irish Terrier. Ultrasonographic examination revealed an elongated tumor along the trajectory of the tibial nerve at the medioplantar aspect of the talocrural joint in an English Cocker Spaniel. Ultrasonographic examination and MRI revealed an elongated tumor along the trajectory of the median nerve at the mediopalmar aspect of the carpus in a Labrador Retriever.

The Irish Terrier with a NST at level C1-C2 and two dogs with a brachial plexus tumor were euthanized at the request of the owner. Five dogs underwent surgical exploration and tumor resection sparing the limb. Histopathological examination of surgical specimens revealed a schwannoma (spinal cord, brachial plexus), a low-malignant neurofibrosarcoma (S1 nerve root, median nerve) and a myxosarcoma (tibial nerve). Follow up examination showed a recurrence in 3 dogs at 2 to 5 months after surgery. Two dogs (C6 spinal cord NST and S1 nerve root NST) were euthanized at the time of recurrence. The Labrador Retriever with a median NST was successfully re-operated. Two dogs with a brachial plexus NST and a tibial NST went into full remission. The dogs that underwent resection of NSTs of median nerve and tibial nerve at distal limb showed no significant neurological deficits following surgery due to overlapping innervation of other peripheral limb nerves.

References

1. Wheeler SJ, SharpNJH. Small Animal Spinal Disorders. Diagnosis and Surgery. Mosby-Wolfe, London, 1994.

2. Jeffery ND. Handbook of Small Animal Spinal Surgery. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, 1995.

3. Bradley RL, Withrow SJ, Snyder SP. Nerve sheath tumors in the dog. JAAHA 1982;18:915-921.

4. Targett MP, Dyce J, Houlton JEF. Tumours involving the nerve sheaths of the forelimb in dogs. J Small Anim Pract 1993;34:221-225.