Theresa W. Fossum, DVM, PhD, DACVS

Tom and Joan Read Chair in Veterinary Surgery, Director, Clinical Programs and Biomedical Devices, Michael E. DeBakey Institute Professor of Surgery, Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine, College Station, TX, USA

Classically, GDV syndrome is an acute condition with a mortality rate of 20% to 45% in treated animals. The gastric enlargement is thought to be associated with a functional or mechanical gastric outflow obstruction. The initiating cause of the outflow obstruction is unknown; however, once the stomach dilates, normal physiologic means of removing air (i.e., eructation, vomiting, and pyloric emptying) are hindered because the esophageal and pyloric portals are obstructed.

The cause of GDV is unknown, but exercise after ingestion of large meals of highly processed food or water has been suggested to contribute to it. Epidemiologic studies have not supported a causal relationship between feeding soy-based or cereal-based dry dog food and GDV. However, Irish setters fed a single feed type appear to have an increased risk of GDV compared to those fed a mixture of feed types. Likewise, adding table food or canned food to the diet of large and giant breed dogs is associated with a decreased incidence of GDV. Feeding dry dog foods in which one of the first four ingredients are oils or fats may also increase the risk of GDV. Other contributing causes include an anatomic predisposition, ileus, trauma, primary gastric motility disorders, vomiting, and stress. Recommendations for clients of animals at high risk are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Recommendations for clients.

Feed several small meals a day rather than one large meal.

Feed several small meals a day rather than one large meal.

Avoid stress during feeding (if necessary, separate dogs in multiple-dog households during feeding).

Avoid stress during feeding (if necessary, separate dogs in multiple-dog households during feeding).

Restrict exercise before and after meals (of questionable benefit).

Restrict exercise before and after meals (of questionable benefit).

Do not use an elevated feed bowl.

Do not use an elevated feed bowl.

Do not breed dogs with a first-degree relative that has a history of gastric dilatation-volvulus.

Do not breed dogs with a first-degree relative that has a history of gastric dilatation-volvulus.

For high-risk dogs, consider prophylactic gastropexy.

For high-risk dogs, consider prophylactic gastropexy.

Seek veterinary care as soon as signs of bloat are noted.

Seek veterinary care as soon as signs of bloat are noted.

Generally, with GDV the stomach rotates in a clockwise direction when viewed from the surgeon's perspective (with the dog on its back and the clinician standing at the dog's side, facing cranially). The rotation may be 90 to 360 degrees but usually is 220 to 270 degrees. The duodenum and pylorus move ventrally and to the left of the midline and become displaced between the esophagus and stomach. The spleen usually is displaced to the right ventral side of the abdomen.

Caudal vena cava and portal vein compression by the distended stomach reduces venous return and cardiac output, causing myocardial ischemia. Obstructive shock and inadequate tissue perfusion affect multiple organs, including the kidneys, heart, pancreas, stomach, and small intestine. Cardiac arrhythmias occur in many dogs with GDV, particularly those with gastric necrosis.

Partial or chronic GDV may occur in dogs and usually is a progressive but non-life-threatening syndrome that may be associated with vomiting, anorexia, and/or weight loss. These dogs may have chronic, intermittent signs and appear normal between episodes. Gastric malpositioning may be intermittent or chronic but without dilatation. Plain or contrast radiographs are diagnostic, but repeat radiographs may be necessary if the stomach is intermittently malpositioned.

Diagnosis

Clinical Presentation

Signalment

GDV primarily occurs in large, deep-chested breeds (i.e., Great Dane, Weimaraner, Saint Bernard, German shepherd, Irish and Gordon setters, Doberman pinscher) but has been reported in cats and small-breed dogs. Shar peis may have an increased incidence compared with other medium-sized breeds. Basset hounds may have a higher risk of GDV, despite their relatively small size. GDV may occur in a dog of any age but is most common in middle-aged or older animals. The thoracic depth to width ratio appears to be highly correlated with the risk of bloat.

History

A dog with GDV may have a history of a progressively distending and tympanic abdomen, or the owner may simply find the animal recumbent and depressed with a distended abdomen. The dog may appear to be in pain and may have an arched back. Nonproductive retching, hypersalivation, and restlessness are common.

Physical Examination Findings

Abdominal palpation often reveals various degrees of abdominal tympany or enlargement; however, it may be difficult to feel gastric distention in heavily muscled large-breed or very obese dogs. Splenomegaly occasionally is palpated. Clinical signs associated with shock may be present, including weak peripheral pulses, tachycardia, prolonged capillary refill time, pale mucous membranes, and/or dyspnea.

Diagnostic Imaging

Radiographs are necessary to differentiate simple dilatation from dilatation plus volvulus. Affected animals should be decompressed before radiographs are taken. Right lateral and dorsoventral radiographic views are preferred in order to facilitate filling the abnormally displaced pylorus with air so that it can be easily identified. The pylorus is normally located ventral to the fundus on the lateral view and on the right side of the abdomen on the dorsoventral view. On a right lateral view of a dog with GDV, the pylorus lies cranial to the body of the stomach and is separated from the rest of the stomach by soft tissue (reverse C sign or double bubble). On the dorsoventral view, the pylorus appears as a gas-filled structure to the left of midline. Free abdominal air suggests gastric rupture and air within the wall of the stomach indicates necrosis, both of which warrant immediate surgery.

Medical Management

Stabilizing the patient's condition is the initial objective. Either isotonic fluids (90 ml/kg/hour), hypertonic 7% saline (4 to 5 ml/kg over 5 to 15 minutes), hetastarch (5 to 10 ml/kg over 10 to 15 minutes) or a mixture of 7.5% saline and hetastarch (dilute 23.4% saline with 6% hetastarch until you have a 7.5% solution; administer at 4 ml/kg over 5 minutes) is administered. Blood should be drawn for blood gas analyses, a CBC, and a biochemical panel. Broad-spectrum antibiotics (e.g., cefazolin, ampicillin plus enrofloxacin) should be administered. If the animal is dyspneic, oxygen therapy may be given by nasal insufflation or mask. Gastric decompression should be performed while shock therapy is initiated.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery should be performed as soon as the animal's condition has been stabilized, even if the stomach has been decompressed. Rotation of an undistended stomach interferes with gastric blood flow and may potentiate gastric necrosis.

The goals of surgical treatment are threefold: 1) to inspect the stomach and spleen so as to identify and remove damaged or necrotic tissues; 2) to decompress the stomach and correct any malpositioning; and 3) to adhere the stomach to the body wall to prevent subsequent malpositioning.

Upon entering the abdominal cavity of a dog with GDV, the first structure noted is the greater omentum, which usually covers the dilated stomach.

Intraoperative manipulation of the cardia usually allows the tube to be passed into the stomach without difficulty. If adequate decompression is still not achieved or an assistant is not available, a small gastrotomy incision can be performed to remove the gastric contents, although this should be avoided if possible.

Gastropexy

Gastropexy techniques are designed to permanently adhere the stomach to the body wall. The most common indications are GDV (pyloric antrum to right body wall) and hiatal herniation (fundus to left body wall). Numerous gastropexy techniques have been described. Although the strength and extent of adhesions created by these techniques differ, all of them (when properly performed) prevent movement of the stomach

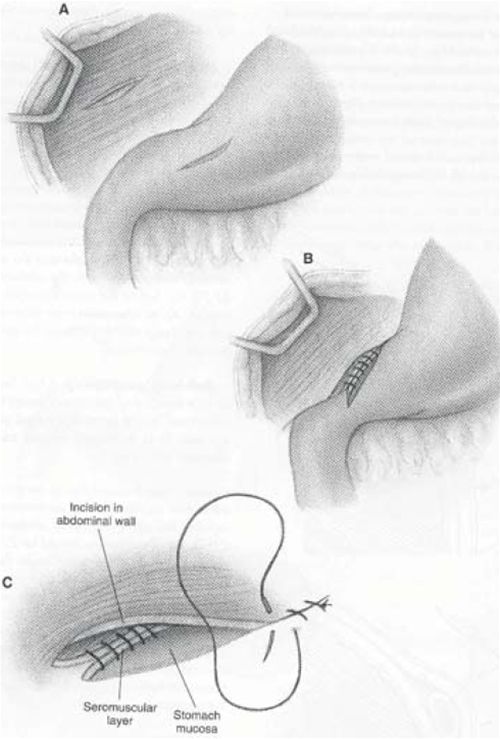

Muscular Flap (Incisional) Gastropexy

Muscular flap (incisional) gastropexy is easier than circumcostal gastropexy and avoids the possible complications associated with tube gastropexy.

Make an incision in the seromuscular layer of the gastric antrum. Then make an incision in the right ventrolateral abdominal wall by incising the peritoneum and internal fascia of the rectus abdominis or transverse abdominis muscles. Suture the edges of the incisions in a simple continuous pattern using 2-0 absorbable or nonabsorbable suture. Make sure the muscularis layer of the stomach is in contact with the abdominal wall muscle. Suture the cranial margin first, then the caudal margin. As an alternative, you may raise flaps in the stomach and body wall to increase the extent of muscle contact between these tissues.

| Figure 1. |

From: Fossum, TW: Small Animal Surgery, Mosby Publishing Co., St. Louis, Mo, 2002 |

|

| |