Theresa W. Fossum, DVM, MS, PhD, DACVS

INTESTINAL RESECTION AND ANASTOMOSIS

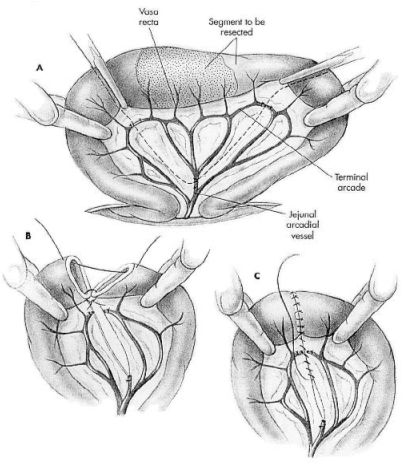

Intestinal resection and anastomosis are recommended for removing ischemic, necrotic, neoplastic, or fungal-infected segments of intestine. Irreducible intussusceptions are also managed by resection and anastomosis. End-to-end anastomoses are recommended.

Make an abdominal incision which allow complete exploration of the abdomen. Perform a thorough examination of the abdomen and collect any nonintestinal specimens. Exteriorize and isolate the diseased intestine from the abdomen by packing with towels or laparotomy sponges. Assess intestinal viability and determine the amount of intestine needing resection. Double ligate and transect the arcadial mesenteric vessels from the cranial mesenteric artery that supplies this segment of intestine. Double ligate the terminal arcade vessels and vasa recta vessels within the mesenteric fat at the points of proposed intestinal transection. Gently milk chyme (intestinal contents) from the lumen of the identified intestinal segment. Occlude the lumen at both ends of the segment to minimize spillage of chyme. Place forceps across each end of the diseased bowel segment. Transect the intestine with either a scalpel blade or Metzenbaum scissors along the outside of the forceps. Make an oblique incision across the intestine if the luminal diameters are the same. When two pieces of intestine are being joined that are of unequal size, use a perpendicular incision across the intestine with the larger luminal diameter and an oblique incision (45- to 60- degree angle) across the intestine with the smaller luminal diameter to help correct size disparity). Make the oblique incision such that the antimesenteric border is shorter than the mesenteric border. Suction the intestinal ends and remove any debris clinging to the cut edges with a moistened gauze sponge. Trim everting mucosa with Metzenbaum scissors just before beginning the end-to-end anastomosis.

Use 3-0 or 4-0 monofilament, absorbable suture (polydioxanone or polyglyconate) with a swaged-on taper or tapercut point needle. Place simple interrupted sutures through all layers of the intestinal wall. Angle the needle so the serosa is engaged slightly further from the edge than the mucosa. This helps reposition everting mucosa within the lumen. Tie each suture carefully so as to gently appose the edges of the intestine with the knots extraluminally. Appose intestinal ends by first placing a simple interrupted suture at the mesenteric border and then placing a second suture at the antimesenteric border approximately 180 degrees from the first (this divides the suture line into equal halves and allows determination of whether the ends are of approximately equal diameter). The mesenteric suture is the most difficult suture to place in the anastomosis because of mesenteric fat. It is also the most common site of leakage. If the ends are of equal diameter, space additional sutures between the first two sutures approximately 2 mm from the edge and 2 to 3 mm apart. If minor disparity still exists between lumen sizes, space the sutures around the larger lumen slightly further apart than the sutures in the intestine with the smaller lumen. To correct luminal disparity that cannot be accommodated by the angle of the incisions or by suture spacing, resect a small wedge (1 to 2 cm long and 1 to 3 mm wide) from the antimesenteric border of the intestine with the smaller lumen. After suture placement inspect the anastomosis and check for leakage. While maintaining luminal occlusion adjacent to the anastomotic site, moderately distend the lumen with sterile saline, apply gentle digital pressure, and observe for leakage between sutures or through needle holes. Close the mesenteric defect with a simple continuous or interrupted suture pattern (4-0 polydioxanone or polyglyconate) being careful not to penetrate or traumatize arcadial vessels near the defect (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. From: Fossum, TW:Small Animal Surgery, Mosby, 2002. |

|

| |

SEROSAL PATCHING

Serosal patching is placement of an antimesenteric border of the small intestine over a suture line or organ defect and securing it with sutures. Serosal patching serves to provide support, a fibrin seal, resistance to leakage, blood supply to the damaged area, and may prevent intussusception. Patches are commonly used following intestinal surgery when closure integrity is questioned or dehiscence is repaired. Patches which span visceral defects are covered with mucosal epithelium within 8 weeks. Most commonly, jejunum adjacent to the defect or area of questionable viability is used for the serosal patch, although other sources could include stomach, other intestinal segments, or urinary bladder.

Use one or more loops of intestine to form the patch. Use gentle loops to avoid stretching, twisting, or kinking the intestine and mesenteric vessels. If using more than one loop of intestine, suture these loops together before securing the patch to the damaged area. All sutures used to create or secure the patch engage the submucosa, muscularis, and serosa; they should not penetrate the intestinal lumen. Place interrupted or continuous sutures in healthy tissue to secure the patch and isolate the damaged area.

BOWEL PLICATION

Bowel plication is performed to prevent recurrence of intussusception; without plication the incidence of repeat intussusception in dogs is relatively high. Serosa-to-serosa adhesions are formed by suturing adjacent loops of intestine together. The small intestine from the duodenocolic ligament to the ileocolic junction should be sutured to decrease the potential for intestinal strangulation. Place small intestinal loops side-by-side to form a series of gentle loops from the distal duodenum to the distal ileum. Secure the loops by placing sutures which engage the submucosa, muscularis, and serosa, 6 to 10 cm apart. Use 3-0 or 4-0 monofilament absorbable or non-absorbable sutures with a taper point swaged-on needle. Avoid positioning the intestinal loops at acute angles lest intestinal obstruction occurs. The adhesions formed by this procedure are probably not permanent adhesions, but they are sufficient to prevent recurrent intussusception.

COLOPEXY

Colopexy is done to prevent caudal movement of the colon and rectum and is especially useful in animals with recurrent rectal prolapse. The procedure creates permanent adhesions between the serosal surfaces of the colon and abdominal wall. Incisional and non-incisional techniques have been described and both are equally effective. A potential complication (but rare if the technique is performed properly) is infection as a result of suture penetration into the colonic lumen.

Expose and explore the abdomen. Locate and isolate the descending colon from the remainder of the abdomen. Pull the descending colon cranially to reduce the prolapse. Verify prolapse reduction by having a non-sterile assistant inspect the anus visually and perform a rectal examination. Make a 3 to 5 cm longitudinal incision along the antimesenteric border of the distal descending colon through only the serosal and muscularis layers. Create a similar incision on the left abdominal wall several centimeters lateral (2.5 cm) to the linea alba through the peritoneum and underlying muscle. Appose each edge of the colonic and abdominal wall incisions with 2 simple continuous or simple interrupted rows of sutures using 2-0 or 3-0 monofilament absorbable (e.g., polydioxanone or polyglyconate) or nonabsorbable (nylon, polypropylene) suture material. Engage the submucosa as each suture is placed. Lavage the surgical site and surround it with omentum prior to abdominal closure. Alternatively, scarify an 8 to 10 cm antimesenteric segment of the descending colon by scraping the serosa with a scalpel blade or rubbing it with a gauze sponge. On the left abdominal wall opposite the prepared colon, scarify the peritoneum in the same manner. Preplace, then tie, 6 to 8 horizontal mattress sutures between the two scarified surfaces. Roll the colon toward the midline and place a second row of 6 to 8 sutures. Use 2-0 to 3-0 monofilament absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures which engage the submucosa, but do not penetrate the colonic mucosa. Tie the sutures apposing the scarified surfaces (see Figure 2).

|

Figure 2. From: Fossum, TW: Small Animal Surgery, Mosby 2002. |

|

| |

POSTOPERATIVE CARE AND ASSESSMENT

The abdominal incision should be checked twice daily for evidence of redness, swelling, or discharge. If the animal licks or chews at the incision, an Elizabethan collar or sidebar should be used to prevent iatrogenic suture removal. Early signs of altered wound healing are inflammation and edema. Serosanguineous drainage from the incision and swelling are consistent signs of acute incisional dehiscence. Dehiscence usually occurs 3 to 5 days postoperatively when minimal healing has occurred and the sutures have weakened; however, it may occur earlier if knots were tied improperly or if fascia was not incorporated into the sutures. Evisceration usually results in sepsis and severe blood loss secondary to mutilation of exposed intestine and must be treated promptly. The abdomen should be bandaged, fluid therapy initiated, and broad-spectrum antibiotics given while the animal is prepared for surgery. If technical failure is suspected (i.e., poor knot tying, improper suturing), the entire suture line should be removed and replaced. Debridement of the wound edges is not necessary and will delay wound healing. The intestine should be closely inspected for viability and damaged sections resected if appropriate. The abdominal cavity should be lavaged with copious amounts of warmed, sterile saline. Open abdominal drainage should be considered in animals with generalized peritonitis. Wound disruption after 10 to 21 days usually results in hernia formation rather than evisceration.