Small Animal Surgery, School of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences, Division of Health Sciences, Murdoch University

Murdoch, Australia

Introduction

The aim of cruciate surgery is to resolve stifle joint instability, manage any concurrent meniscal injuries and possibly reduce the progression of osteoarthritis (OA)1. Controversy exists over whether there is an 'ideal' cruciate surgery technique2. New cruciate surgery techniques continue to be developed.

All surgical techniques have associated complications. Some complications are common to all cruciate surgeries while some are specific to a particular procedure. Reported complication rates following cruciate surgery up to 32% have been reported and include late meniscal injury, joint or soft tissue infection, osteomyelitis, seroma, screw loosening, fracture (tibia, fibula, patella), distal limb oedema, implant failure, patella luxation, neurological deficits, wound dehiscence, patella tendon desmitis and intraoperative haemorrhage. Valid comparison of complication rates of the various techniques is difficult due to multiple variables and differing interpretation of data. Consideration of complications specific to cruciate osteotomies is beyond the scope of this paper. The purpose of this paper is to outline a practical approach to diagnosing general cruciate complications.

The most commonly reported complications are incisional (wound discharge, dehiscence, seroma), infection (periarticular soft tissue, implant, joint, osteomyelitis) and late meniscal injury (meniscal injury that occurs subsequent to cruciate surgery where the meniscus was correctly determined to be normal or where a meniscal injury was appropriately treated).

Lameness outcomes following cruciate surgery are reported to be subjectively good however it is important to consider what realistic expectations we should be giving owners of dogs undergoing cruciate surgery. The majority of cruciate instability results from cruciate disease (progressive pathologic degenerative cruciate rupture with OA rather than traumatic cruciate rupture2,3. While the ideal cruciate surgery will resolve stifle joint instability it will not resolve the OA and not surprisingly has been shown to result in only a small percentage of dogs returning to normal function when assessed objectively on a force platform2. Furthermore dogs that require caudal pole hemimeniscectomy can be expected to have more rapid progression of OA and greater morbidity than dogs with intact menisci4,5.

Assessment

The first step in assessing dogs that are not progressing as well as expected post surgery or have had an acute deterioration in improvement is a complete history, thorough physical examination (including an orthopaedic and spinal neurologic examination) and observation of gait to confirm that the stifle joint remains the site of lameness.

Radiography is essential to assess any implants and rule out radiographic evidence of fracture, osteomyelitis or neoplasia. MRI, arthroscopy and ultrasound have been shown to have high specificity and sensitivity for detecting meniscal injury in dogs though remain currently limited by expense, availability and technical expertise.

Arthrocentesis

Arthrocentesis and synovial fluid analysis are simple and quickly provide information to differentiate the presence of infection or other inflammatory joint diseases.

The stifle joint is clipped and surgically prepared. Draping is not necessary however the use of sterile surgical gloves is recommended. The femorotibial joint space is an easy space to penetrate however collection of fluid is often limited due to the fat pad. Where a palpable joint effusion exists (virtually all cases of cruciate disease) collecting from the femoropatellar joint pouch is easier and provides good volumes of fluid. The needle is inserted lateral to the distal pole of the patella and trochlea ridge and directed dorsally and superficially towards the lateral femoral condyle--this area is not covered in articular cartilage.

If small volumes (<0.2ml) are obtained these should be assessed immediately for colour, clarity and viscosity prior to making a direct smear by a 'squash' preparation. (Put a drop of synovial fluid on the slide then lay a second slide flat on top of it. Slowly slide them apart--this makes thin smears which are easier to interpret).

If larger volumes are collected a direct smear is made and the remainder submitted for analysis. EDTA is the preferred anticoagulant for cytological examination while heparin is preferred for a mucin clot (viscosity) test.

If a septic arthropathy is suspected synovial fluid should be submitted for aerobic and anaerobic culture in blood culture bottles (usually 5 ml of synovial fluid is required--check with your laboratory first) or in appropriate transport media.

Table 1. Normal parameters of synovial fluid.

|

Volume

(ml) |

Colour |

Clarity |

Viscosity |

Mucin

clot |

Cell

count

x 109/L |

Mononuclear

cells

(%) |

Neutrophils

(%) |

|

0.01-1.0 |

None to light yellow |

Clear |

Good |

Good |

< 3.0 |

90-100 |

0-10 |

Synovial fluid in cruciate disease is non-inflammatory--typical of OA. It is usually of increased volume, slightly decreased viscosity and mildly altered colour. Total nucleated cell count (TCC) and differential cell count are usually within the normal range (Table 1). Synovial fluid protein levels are slightly increased above 25 g/L.

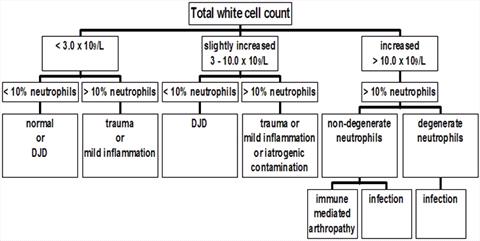

Bacteria are rarely observed in a smear of septic synovial fluid. Despite reports to the contrary, neutrophils from a septic inflammatory arthropathy are very commonly non-degenerate on cytological examination6. Neutrophil degeneration suggests sepsis. Septic fluid is turbid, with poor viscosity, high neutrophils percentage and high TCC (Figure 1). Post cruciate surgery infections commonly present without overt clinical signs of sepsis. Dogs typically will present with chronic lameness and failure to have improved as anticipated +/- vague malaise. Discharging sinuses are infrequently seen today since monofilament leader line has largely replaced multifilament material for extracapsular repair.

Click on the figure to see a larger view.

| Figure 1. |

Algorithm for interpreting synovial fluid total and differential cell counts. |

|

| |

Meniscal Injury

Late meniscal injury typically presents as an acute deterioration in lameness and can occur at any time post cruciate surgery (occurrence ranges in two studies 2-28 months)7,8. Late meniscal injury (reported in 4-22% of cases post cruciate surgery depending on the surgical technique) suggests ongoing stifle joint instability and should be differentiated from untreated meniscal injury at the time of cruciate surgery. Dogs with untreated meniscal injuries typically have persistent lameness post surgery. In both instances physical examination primarily reflects the underlying cruciate disease (joint enlargement from periarticular fibrosis and joint effusion, reduced range of motion and pain on manipulation) rather than being diagnostic of meniscal injury. A meniscal 'click' is neither sensitive nor specific for meniscal damage. Presence of an audible or palpable meniscal click indicates condylar subluxation at the very least and the presence of meniscal damage must be ruled out.

The presence of meniscal injury can be determined through arthrotomy, arthroscopy, ultrasound or MRI. Arthroscopic examination is considered to be the 'gold standard' for detection of meniscal injury and may be superior to examination at arthrotomy.

Lack of expected improvement or acute deterioration in progression post surgery indicates the need for further investigation and elimination of the possibilities of meniscal injury, infection or other causes. Severity of OA and presence and severity of any meniscal injury can be expected to influence outcome.

References

1. Piermattei DL, Flo GL, DeCamp CE. The stifle joint, in: Handbook of Small Animal Orthopedics and Fracture Repair 4thedn. Phil., PA, Saunders, 2006, pp 562-632

2. Conzemius MG, Evans RB, Besancon MF, et al. Effect of surgical technique on limb function after surgery for rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament in dogs. J Am VetMed Assoc 226:232-236, 2005

3. Hayashi K, Manley PA, Muir P. Cranial cruciate ligament pathophysiology in dogs with cruciate disease: a review. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 40:385-390, 2004

4. Johnson KA, Francis DJ, Manley PA, et al. Comparison of the effects of hemi-meniscectomy and complete meniscectomy in the canine stifle joint. AJVR;65:1053-1060, 2004

5. Pozzi A, Litsky AS, Field J, et al. Pressure distributions on the medial tibial plateau after medial meniscal surgery and TPLO in dogs. VCOT, 21:8-14, 2008

6. Marchevsky AM, Read RA. Bacterial septic arthritis in 19 dogs. Australian Veterinary Journal.; 77(4): 233-237, 1999

7. Pacchiana PD, Morris E, Gillings SL, et al. Surgical and postoperative complications associated with TPLO in dogs with cranial cruciate ligament rupture: 397 cases (1998-2001). J Am Vet Med Assoc 222:184-193, 2003

8. Thieman KM, Tomlinson JL, Fox DB, et al. Effect of meniscal release on rate of subsequent meniscal tears and owner assessed outcome in dogs with cruciate disease treated with TPLO. Vet Surg 35:705-710, 2005